Chicago bicyclist Neill Townsend, 32, killed by semitrailer while swerving to avoid a white Nissan Altima car door at 9:00am in the morning

There was only about five feet between the line of parked cars and the semitrailer — and no room for error. Into that narrow space rode a bicyclist, a lawyer who was on his way to work at 9 a.m. Friday.

Along the curb, a driver had just parked his white Nissan Altima. He put his hand on the car door and pushed it open.

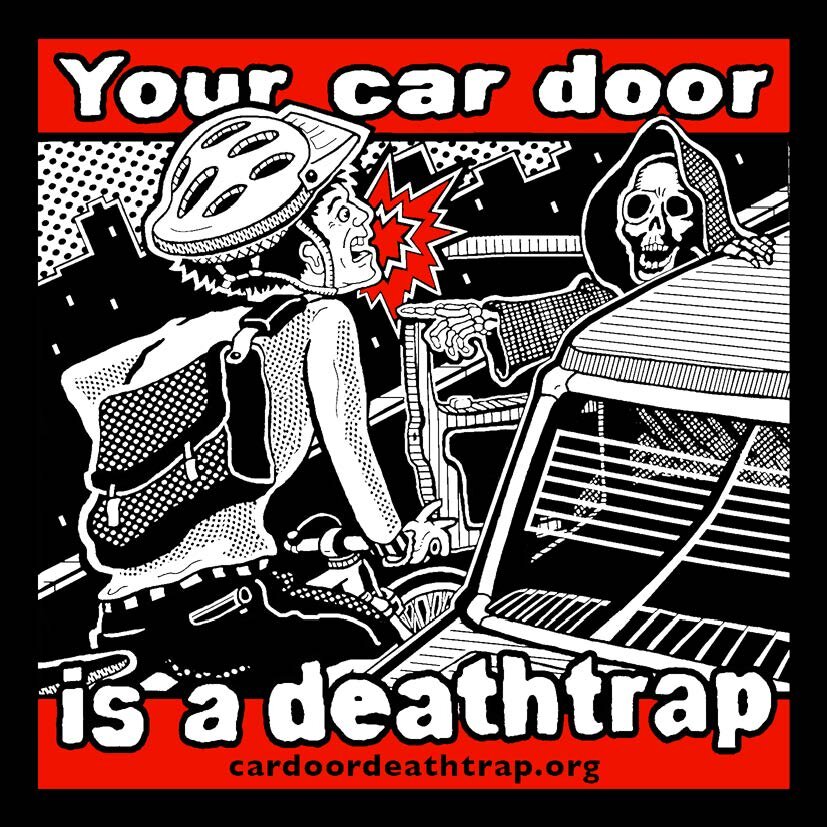

That small act — the opening of a car door — is something many of us do every day without thinking, and often without looking. But on this morning, it had deadly consequences.

The semi was passing. The car door was opening. The bicyclist, caught in between, swerved and fell under the wheels of the truck.

The victim was identified as Neill Townsend, 32, a North Side resident who bicycled to work almost every day in all weather. He was killed as he rode southbound on North Wells Street just north of Oak Street.

Neill Townsend

The driver of the Nissan, Alexander Squiers, 22, of the 1000 block of West Wellington Avenue, was cited by police with violating a 2008 ordinance intended to protect bicyclists.

After the collision, Squiers, who police said was very shaken, remained in the area cordoned off by yellow tape, showing officers what had happened, opening his car door several times. A black bicycle lay on the ground nearby.

“This is why I don’t ride a bike in the city. I’m too afraid,”

said Tara Werling, 18, shivering as she stood near the scene of the collision. "The bike lanes are too narrow. You're right up against the cars. If someone opens a door, you have to swerve."

And, she added, "no helmet is going to save you when you go up against a car."

In recent years, Chicago has attempted to transform itself into a bike-friendly city. Mayor Rahm Emanuel ran on a platform that included promises to add 100 miles of protected bike lanes in his first four years in office.

Last summer, the city's first protected bicycle lane, which separates cyclists from vehicles, opened along a half-mile stretch of Kinzie Street. And next spring, a much-heralded bike-share program that will allow people to check out bicycles in one area and drop them off in another is scheduled to kick off.

But on city streets crowded with people, cars and bicycles, there often is just not enough room.

Bicyclists say they perform a careful calculus each day, hugging the shoulder to stay out of traffic while also keeping a wary eye on lines of parked cars. At any moment, a car door could open into their path without warning, leading to a collision known by bicyclists as getting "doored."

"Every time I bike, someone opens the door without looking," said Chelsea Gebhardt, 27, a nurse who bikes three times a week along the stretch of Wells Street where Friday's collision occurred. "I end up yelling and the drivers usually look startled and apologize."

"A nurse I worked with got doored last year and broke her jaw. It needed to be wired shut," Gebhardt said. "She won't ride anymore. She's too traumatized."

Running into the just-opened door of a parked vehicle is among the most feared and most common incidents between cars and bicycles, biking advocates and transportation officials said.

To address the issue, wording was added to the city code in 2008 making anyone found guilty of opening a car door into traffic, causing a collision with a bicycle, eligible for a $500 fine. Last year for the first time, the Illinois Department of Transportation began requiring police departments across the state to record dooring accidents on state traffic crash forms.

“Last year (2011), 337 dooring crashes were reported in Chicago, and 117 were reported through June 30, 2012, according to IDOT officials.”

The block of Wells where the collision occurred is considered a relatively safe stretch for bikers. It is flanked on both sides by bike lanes that make it a central route for bicyclists, many of whom use it to travel between the North Side and downtown.

Because of the corridor's popularity, the city had planned to widen the bike lanes on Wells next year to provide more space between bicyclists and parked cars, according to Chicago Department of Transportation spokesman Pete Scales. "It is identified as a crosstown route and the street is wide enough to accommodate it," said Scales.

Cycling advocates say wider lanes can be crucial in protecting bicyclists.

"The alternative design is to either build a bike lane that is wider or to the right side of the (parked) car," said Steven Vance, a Chicago-based blogger and biking advocate. "A protected or wider bike lane may have prevented this from happening."

In August, Emanuel announced that the city will build more than 30 miles of new bicycle lanes in Chicago this year, a move that has been largely championed by the city's cycling community. The lanes will be a mix of the regular bike lanes, buffered lanes that are wider, and protected lanes, which typically feature barriers between traffic and bicycles, according to Scales.

Planners have to take many aspects into consideration when determining what type of bike lane will work for a given stretch of road. "Traffic counts and the size of the roadway are big factors," Scales said. "But, also, destinations along the route and the connectivity of the different routes together."

Friends of Townsend, who lived in the 1500 block of North LaSalle Drive, said he was an avid biker. Co-workers suspected something was wrong when he didn't show up at a morning meeting at a coffee shop. "He's always on time," said Scott Wilson, CEO of Minimal Inc. in the West Town neighborhood.

The head of operations at the design firm for the last two years, Townsend had joined the company as a consultant.

"He always had great ideas,'' Wilson said. "I'm just glad I got to know him. He will be greatly missed, both as an employee and as a friend. He had so much potential."

By Colleen Mastony, Cynthia Dizikes and Rosemary R. Sobol, Chicago Tribune reporters

Tribune reporters Lolly Bowean and Jeremy Gorner contributed.

cmastony@tribune.com, cdizikes@tribune.com, rsobol@tribune.com

Related Articles:

A Teachable Moment Arises From Death Of Chicago Bicyclist